Icons have been described as “Theology written in images and colour.” Icons are not just pictures — they are sacred images, which convey spiritual truth in picture form, and are sometimes described as windows to heaven. Let's learn some more about what icons are, how they are made, the symbolism involved, and why some people protested against them!

What is an Icon?

Icons are aids to worship. The purpose of an icon is to give a message which requires inner hearing and inner seeing. Any place where an icon is set more easily becomes an area of prayer. Many Orthodox have an icon corner in their home around which a devout family would gather for prayer. Some icon corners also have oil lamps and prayer books, palm crosses or flowers from the paschal season and maybe some blessed water from Theophany.

![]()

Orthodox Christians honour icons but don’t worship them. Icons are not idols because it is not the wood, canvas or paint that is being honoured. All the honour passes to the prototype (i.e. the person depicted by the icon). In other words, someone bowing before an icon of Christ and kissing it is expressing his or her love for the Saviour, much as you might kiss a photo of your husband or wife when apart.

Take for instance the Theotokos with child (Theotokos is a Greek word meaning “God-bearer” and refers to Mary) in the Apse (the area of the wall just above the holy table in most Orthodox Churches). Christ is depicted in the area of her heart. This icon conveys our purpose in life: it shows Mary with her arms outstretched, summoning us to respond to the call of God with the same faith and obedience with which she herself responded, in order that Christ may be formed in us as He was formed in her. She is showing us that a Christian is one in whom Christ lives. She invites us to receive within us, by faith and by the Eucharist, the Christ who was conceived and formed in her so that we, too, may become “God-bearers.”

St. Paul often refers to the topic of Christ living within us. In fact his whole message centres around the indwelling Christ. Galatians 4:19 is an example:

My little children, with whom I am again in travail until Christ be formed in you.

The Theotokos is not usually portrayed alone in icons but with Christ. They are in fact “incarnation icons.” Venerating them, we express reverence and awe before the humanity of God; we see God in the form of a baby, held in His Mother’s arms. This is why the priest venerates the icon of the Mother and Child during the Divine Liturgy.

Making Icons

There is a sacramental quality to the work of making icons; in fact, icons are said to be written rather than painted because of the teaching they contain.

The writer only approaches the task after study, meditation and prayer, and sometimes fasting. There are prayers for the pardoning of enemies to ensure that the Iconographer is at peace (because the state of the soul will show in the painting).

The act of painting is done according to the strictest rules. There is a correct way to represent human figures and background — using prototypes so that the believer is immediately able to recognise and respond to an icon of say “Christ’s Nativity” or “The Ascension” or “John the Baptist.” Reverse perspective is always used, so things don’t taper into the distance but put the observer on the same plane as the Saviour, Saint or event.

The faces are not depicted naturally because they are supposed to convey the person as “beyond this world” in the presence of Christ.

Symbolism in Icons

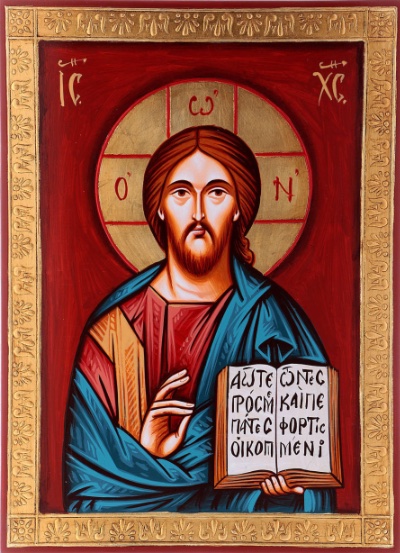

There is a wealth of symbolism in icons. For example, the halo around the head of a Saint denotes the light of Christ shining from within. A blue garment indicates humanity and red indicates divinity. Thus, Christ has a red undergarment and a blue outer garment, because He is divine and put on humanity. Mary, on the other hand, has a blue undergarment and a red outer garment, as she was human but she became divine by bearing Christ.

![]()

Buildings in icons cast no shadows, since shadows indicate sun passing through the sky; the icon picture is meant to have a spiritual, timeless quality.

The monogram IC XC is composed of the first and last letters of Jesus Christ in Greek (iota and sigma meaning “Jesus” and chi and sigma meaning “Christ”). The sigmas are both rendered in “C” form, resulting in “IC XC.” This monogram is commonly written on icons of Christ near His halo to identify Him. It sometimes appears in the phrase “IC XC NIKA,” meaning “Jesus Christ Conquers.”

The letters traditionally written on the cross in Christ’s halo are a reference to the name of God revealed to Moses during the burning bush episode (Exodus 3:14). This name was “I am” or “I am that I am.” So this reminds us that Jesus is “The One who is God.”

Iconoclastic struggles

In 725 A.D. the Emperor of Constantinople — Leo III — ignoring opposition from Patriarch Germanus, decided that the making and venerating of icons violated the Old Testament prohibition against graven images. Churches under the Emperor’s rule were obliged to destroy their icons. As a result, early icons are extremely rare. Areas under Muslim rule were not governed by imperial decrees so some icons were saved in those areas. Some were also spared in Rome. The icons that adorn the Basilica of Santa Maria Maggiore date from the mid-fourth century. Even earlier icons survive in Rome’s Catacombs.

St. John of Damascus is known as the great defender of icons from this period. He wrote at length on their meaning. The following quote is from his writings On Divine Images:

In former times God, who is without form or body, could never be depicted. But now when God is seen in the flesh conversing with men, I make an image of the God whom I see. I do not worship matter; I worship the creator of matter who became matter for my sake...

St. John also pointed out that when God appointed in the Church first apostles, secondly prophets, and thirdly pastors and teachers, for the equipping of the saints, He did not say Emperors!

The first period of icon destruction (known as Iconoclasm) lasted until 780. Another, less severe wave initiated by Emperor Leo V in 813, followed it. Resistance grew and included an icon-bearing procession in Constantinople by a thousand monks. Objections ended in 842. A council was convened to reaffirm the teachings of the Seven Ecumenical Councils, so confirming the place of icons in Christian life. The first Sunday of Great Lent was set aside to celebrate this Triumph of Orthodoxy, a custom maintained to this present day. Iconoclastic attitudes still haunt other forms of Christianity though there is, currently, a revival of interest in icons across all denominations and a proliferation of books on the topic.

Learn More

Blogs

Books

- Icons: The Essential Collection

- The Resurrection and the Icon

- Doors of Perception: Icons and Their Spiritual Significance

Audio

Video